By Kathryn Washington, EdD, Kelly Brown, EdD, and Sharon Ross, EdD

“The world turned upside down” (Miranda, 2015) is a quote from the popular musical Hamilton based on the Founding Fathers fight for our nation. Today during this pandemic and civil unrest, it seems the world is upside down again. With the fluidity and demands of COVID-19, in combination with a modern-day Civil Rights movement, leaders are challenged with how to address the needs of students and families. Building and sustaining relationships with all stakeholders will be the key for leading your organization forward during times of crisis. In The Leadership Challenge (Kouzes & Posner, 1987, p.19) the authors remind us, “When leadership is a relationship founded on trust and confidence, people take risks, make changes, keep organizations and movements alive.”

How to Build Relationships and Trust

The collaboration between relationships and trust are warranted to successfully lead all stakeholders and community to meet students’ educational needs. Relationship and trust are defined as the way in which people relate to a firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability or strength of someone. Fairholm writes, “Leadership is something that happens as a result of leader and stakeholder collaborative action. Leadership is not a starring role. True leadership describes unified action of leaders and followers (stakeholders) working together to jointly achieve mutual goals.”(Leadership and The Culture of Trust, p. 3). If done right, these collaborations of relationships and trust will dictate the outcomes of an organization in a positive way (Schaefer, 2015).

In building relationships and trust, it is also important to have credibility on a personal level. Credibility is built on the culture of one’s reputation within an organization. Reputation directly reflects on credibility and needs to be present before any interactions a leader might have. When credibility and reputation are on a high level, the relationship of trust can be established faster (Covey, 2019). During a crisis, the faster leaders can build trusting relationships, the better it will be for the organization due to the many changes that are being required daily.

Where to begin? A question on Twitter to teachers on what advice they would give a new administrator regarding the building of relationships and trust (Garcia, 2020) garnered an overwhelming response. More than half of teachers responded that leaders need to listen and talk less. Listen to all stakeholders to hear their needs and work together on a solution. While collaborating, grow and stretch your organization to build future leaders who will continue the work toward success.

Relationship Oriented Leadership

The ability of leaders to build relationships amongst staff has various effects on the organization. It improves trust and adds to the staff’s perception of the leaders’ effectiveness. There are two types of behavioral roles leaders can adopt (Stogdill, 1950), task-oriented leadership and relationship-oriented leadership. More specifically, task-oriented leadership is when the leader focuses on clear constructs regarding the role of workers and how goals are to be achieved. Whereas, relationship-oriented leaders can focus on the well-being of workers and demonstrate concern and respect, appreciation and support for their workers (Bass, 1990). The relationship-oriented leaders believe this approach will yield results toward stated goals and achievements. The research shows consideration towards workers, as well as creating opportunities for groups to attain goals are necessary components of effective leadership (Tabernero, et.al., 2009).

With the current crisis at hand, leadership will define how various organizations navigate and address problems as bridges instead of barriers. It is critical for leaders to work to build relationships because trust, support, motivation and personal development (Yilmaz, 2019) will be vital in the months to come. One of the main reasons for this focus on leadership is:

the emergence of empowerment, increased competition in organizations and the need for innovation and freedom, increased the importance of the individual and therefore the need to ensure their participation in decisions for the increase of productivity, the need to develop the strategic importance of organizations to improve the product and service to create (Çavuş, 2008: 1289).

The basis of all relationships is trust, as it provides greater confidence and productivity (Mishra and Morrisey, 1990). In other words, the relationship of the leader and the amount of trust in the leader and the organization have a symbiotic relationship. When a crisis or chaos happens inside or outside of an organization, relationships and trust become the bedrock to move forward. In addition, research on trust highlights a strong link between the trust in the leader and the support of employees, as well as willingness to follow instructions (Brockner, et al., 1997). In 2020, when the pandemic hit, educators had to step up to address learning in a very new environment. Despite this current crisis, leadership has always been a vital part of the success of the organization. Success will now look like innovation, creativity and flexibility but only if framed around relationships and trust with leadership and the community.

Lack of Relationships and Trust

Trusting relationships is a mitigating factor to teacher burnout. Burnout or occupational stress can occur when teachers do not feel supported by supervisors or coworkers, feel as if they have little control over work processes, or find their efforts on the job are incommensurate with the job’s rewards (WHO, 2015). Many teachers leave the profession each year because of job-related stress caused by everything from student behavior to lack of administrative support. Other stressors are low salaries, lack of school resources to meet the needs of the students, and reform with demanding quick turnaround. Teachers are exhausted and dissatisfied when they come to the realization the organizational setup does not support meeting student needs and expectations (Santoro, 2019). Occupational stress is even greater for school leadership. The challenges and demands on even effective leaders are so overwhelming that, just like teachers, they may increasingly question their career decisions (Kafele, 2018).

Research supports the linking of burnout with turnover (Siefert, Jayaratne, & Chess, 1991), negative behaviors on the job (Randall & Scott, 1988), and symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, and other illnesses that could lead to depression (Norcross & Guy, 2007). Burnout amongst frontline staff has been linked with age, training adequacy, and job satisfaction, along with peer and coworker support (Lakin, Leon, & Miller, 2008). As the pandemic and civil unrest continue, an organization cannot afford to lose anyone. It is imperative that leaders find ways to cultivate positive relationships and build a sense of trust to sustain their organizations through this uncertainty.

The Road Ahead

What lies ahead? Although many leadership theories exist, trust is one constant that is common to all leaders. Covey (2008) says lack of trust “destroys the most powerful government, the most successful business and the most influential leadership” (pg.1). In every situation, crisis, epidemic or pandemic, trust impacts group dynamics, relationships between leader and employee, work productivity, the speed of processes and procedures, and outcomes.

When trust is built together with solid principles, with it comes various levels of confidence within the relationships. According to Covey (2008), high trust relationships signify a high level of confidence with the relationship. While suspicion, which destroys organizations, project productivity and team building, signifies a low level of confidence. It is common to experience burnout in a climate of distrust and suspicion. In the current climate of questions regarding the return to learning school environment and what social distancing will present for the average classroom, there will inevitably be uneasiness. Work completed on the front-end regarding relationships and trust will define the levels of stress and even then, some of the stress and burnout has nothing to do with the school leader.

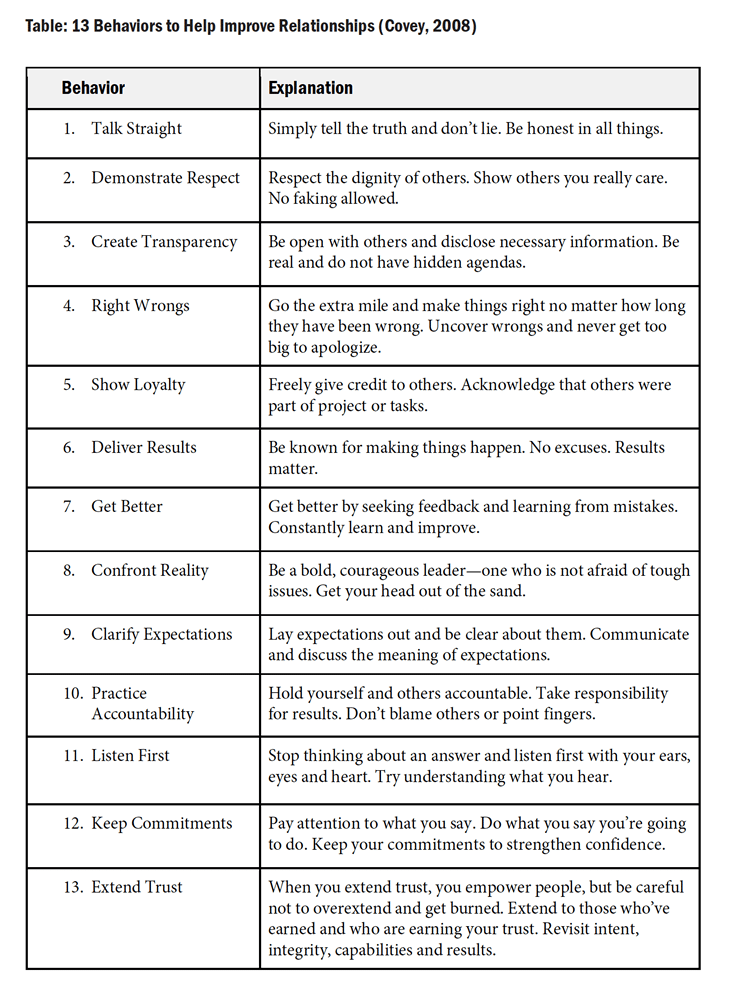

State legislators, government officials and education agencies roll out mandates and guidelines creating unrest, distrust and suspicion. Who should educators, parents, students and constituents believe? Where to start from here and what lies ahead? First, identifying two or three of the 13 behaviors Covey (2008) suggests that will improve relationships, create a plan of action and work on becoming a better leader!

A second consideration for moving forward is for you to examine your leadership style as suggested in Fiedler’s Contingency model. Not all leaders put people first. Some are focused on completing tasks and projects, and do not see the needs of the people involved. Those leaders are not considered relationship-oriented leaders; thus, in hiring, considerations to identify those who display a high level of leader-member trust and confidence. Further, Fernandez and Shaw (2020) highlighted leadership practices displayed during the devastating disruptions of Hurricane Katrina and the current COVID-19 crisis that are indicative of placing the interests and well-being of others above their own. In both cases, educational organizations and their leaders have been left to swiftly abandon the norm and navigate through uncharted territories.

In their article, “Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19,” Fernandez and Shaw (2020) maintain that shared leadership models have shown higher benefits from work that is being produced through collaborative and innovative efforts. These authors present a new toolbox for leaders facing uncertainties. Organizations must be aware of the gaps created between them and success in crisis situations when led by traditional authoritarian and autocratic leaders. The authors further present the need for leaders to show compassion, inspire, allow the knowledge and skills of others to shine, encourage team members to collaborate and invite members from different levels to the table for collaboration to include all stakeholders. Leaders must be able to empower others to lead and find solutions to problems and concerns.

Finally, the article focuses on three best practices for academic leaders when working to build and cultivate positive relationships through trust. Those three practices, as defined by Fernandez and Shaw (2020) are:

- First, connecting with people as individuals and building/establishing trust.

- Second, ensuring that leadership is distributed at all levels of the organization.

- Third, ensuring clear communication occurs throughout the organization, to all stakeholders, on a regular basis.

These are a few suggestions for the road ahead, but clearly dynamic leaders never wait to sharpen their skills. Before, during and after a crisis or pandemic, a skillful leader seizes every moment to build and rebuild relationships, propel the speed of trust, and extend leadership opportunities to others. Leaders do all this while employing self-care to ensure a refueling and reenergizing to continue the journey with so many plans, processes and procedures being discussed, created, questioned, rewritten and revised on a daily basis.

In the book, Training Camp (Gordon, 2009), one chapter points out the faith that greatness requires. And, while one may wonder where greatness fits in a sea of raging storms and virus infected air, the greatness of leaders, though not at the forefront of those individuals, is what carries the organization through the crisis or pulls them under the current. Gordon (2009) encourages individuals to rely on a power greater than themselves by becoming a conductor, letting go and surrendering all pain, fear, anxiety and problems…(pg. 121).

In sharing how to best seize the moment, Gordon (2009) writes: “…rather than hiding from pressure, they (the best) rise to the occasion. As a result, the best defines the moment rather than letting the moment define them. To seize the moment, don’t let your failure define you; let it fuel you. Don’t run from fear, face it and embrace it. …don’t let the moment define you. You define the moment. Define it by knowing that your practice and preparation have prepared you well. Define it with your mental strength, faith, and confidence” (pg. 112).

Dr. Kathryn Washington is an Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership at Lamar University. She also serves as the TEPSA President for Region 6 and TCWSE Vice President. With more than 29 years in education, she served as an elementary principal for 12 of those years where she built strong campus culture and climate based on relationships and trust.

Dr. Kelly Brown is an Assistant Professor in the Center for Doctoral Studies in Educational Leadership at Lamar University. As a former administrator and teacher in the Houston area, she is passionate about ensuring all students have access to a quality education throughout the pipeline. Her research is focused on supporting schools through policy, practice and professional development to achieve equitable outcomes for learners. She is an avid writer, researcher, teacher and advocate for students.

Dr. Sharon Ross is Assistant Professor/Coordinator of MEd Certification & Superintendent Program at Tarleton State University. She successfully led both Jefferson ISD and Mexia ISD as Superintendent. She is also a former elementary classroom teacher and principal, secondary/middle school principal, Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum & Instruction and Adjunct in Educational Leadership. She served as TCWSE President 2018 and is a Member of TABSE, Member of TCPEA, Member of SistersinHigherEd, and Womens Mentoring Network.

References

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press.

Brockner, J., Siegel, P.A., Daly, J.P., Tyler, T. & Martin, C. (1997). When trust matters: The moderating effect of outcome favorability. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 558-583.

Çavuş, M. (2008). Personel güçlendirme: İmalat sanayi işletmelerinde bir araştırma. Journal of Yasar University, 3(10), 1287-1300.

Covey, S. (2019). How the best leaders build trust. Leadership Now. https://leadershipnow.com/CoveyOnTrust.html.

Covey, S. (2008). The speed of trust. New York: Free Press, 1, pp. 127-229.

Fairholm, G. W. (1994). Leadership and the culture of trust. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, p. 3.

Fernandez, A. & Shaw, G. (2020). Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14, 1-7. Online April 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020 from onlinelibrary.wiley.com.

Garcia, E. [@flyingmonkey13]. (2020, May 21). Teachers, what advice would you give a new administrator regarding the building of relationships and trust? Twitter. https://twitter.com/flyingmonkey13/status/1263637512746131456.

Gordon, J. (2009). Training camp: A fable about excellence. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 112.

Kafele, B. (2018). Avoiding school leadership burnout. Educational Leadership: Fighting educator burnout, 75, 22-26. Retrieved July 14, 2020 from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/summer18/vol75/num09/Avoiding-School-Leadership-Burnout.aspx.

Kouzes, J. and Posner, B. (1987). The Leadership Challenge, 3d ed. (John Wiley & Sons, 2006), p. 19.

Lakin, B. L., Leon, S. C. & Miller, S. A. (2008).Predictors of burnout in children’s residential treatment center staff. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 25(3), 249-270.

Miranda, L. (2015). Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down) [Song]. Hamilton. Avatar, NYC; Invictus Sound, Long Island, NYC.

Mishra, J. & Morrissey, M. A. (1990). Trust in employee/employer relationships: A survey of West Michigan managers. Public Personnel Management, 19(4), 443- 485.

Norcross, J. & Guy, Jr. J. (2007) Leaving It at the Office: A Guide to Psychotherapist Self-Care. New York: Guilford Press, p. 238.

Randall, M. & Scott, W. A. (1988). Burnout, job satisfaction, and job performance. Australian Psychologist, 23(3), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050068808255616.

Schaefer, B. (2015). On becoming a leader: Building relationships and creating communities. EDUCAUSE Review, 50(6), 75-78.

Siefert, K., Jayaratne, S. & Chess, W. A. (1991). Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover in health care social workers. Health & Social Work, 16(3), 193–202.

Santoro, D. A. (2019). The problem with stories about teacher “burnout.” Phi Delta Kappan, 101(4), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719892971.

Stogdill, R. M. (1950). Leadership, membership and organization. Psychological Bulletin, 47, 1-14.

Tabernero, C., Chambel, M. J., Curral, L. & Arana, J. M. (2009). The role of task-oriented versus relationship-oriented leadership on normative contract and group performance. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 37(10), 1391–1404. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.10.1391.

WHO. (2015). Stress at the workplace. Retrieved October 27, 2015. https://www.who.int.

Yilmaz, F. (2019). Organizational support and the role of organizational trust in employee empowerment. International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences/Uluslararasi Avrasya Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 10(37), 968–980.

TEPSA Leader, Fall 2020, Vol 33, No. 4

Copyright © 2020 by the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association. No part of articles in TEPSA publications or on the website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association.